I learned at an early age to avoid the fly agaric mushroom. Recognised by a characteristic red cap dotted with white spots, it’s considered poisonous. Carsten Höller, on the other hand, uses it frequently, as an element in his work. His 2010 show Soma presented the following scene: the museum Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin – originally a railway station – split down the middle by a pathway with, in the centre, a mushroom-shaped elevated platform holding a large bed. On either side of the path were two identical but mirrored enclosures, each containing six reindeer walking around giant resin sculptures of fly agaric and other mushrooms. There were also two sets of Timbrado Espanol canaries (24 in total), eight mice and, somewhere, two flies. The participants in this menagerie had been gathered for the purpose of examining the quality of Soma, a drink revered in Vedic [ancient Indian] scripture, which, according to legend, provided its imbibers with divine powers.

The ‘experiment’ is classic Höller: the reindeer in one of the enclosures were fed fly agaric mush-rooms; their urine, as well as that of the reindeer fed on a less toxic diet, was then collected by handlers, refrigerated and passed on to the cana-ries, mice and flies. But which urine, and to which canaries? Impossible to know. On the surface, it looked like a scientific experiment, albeit one with a fine dining restaurant overlooking the spectacle, and the possibility of renting the hotel-standard bed on top of the mushroom-shaped platform for a fee of €1,000 per night.

“It was actually very unscientific, as there were, in a sense, multiple blinds inserted,” says Höller. “There were two groups of reindeer, one being fed the fly agaric mushroom, and one that wasn’t, but only the reindeer keeper knew where he’d put the mushrooms. You could watch the reindeer and the other animals – the test animals – but if you saw something peculiar, or extraordinary, there was no way of knowing whether it was the effect of the mushroom or simply unusual animal behaviour.”

The starting point of the experiment was a theory proposed by R Gordon Wasson in his 1968 text Soma: Divine Mushroom of Im-mortality. In it, Wasson proposes that the lost recipe for Soma could contain the urine of a person who has, in some form, ingested the fly agaric mushroom.

Did you try the reindeer urine yourself?

I did.

And?

It was disgusting. Also, it didn’t work – we should have been more specific about where the fly agaric was picked and what time of the season it was. The toxicity of the mushroom depends a lot on the season and – since it has a symbiotic relationship with the trees it grows with – where it’s picked. It seems they’re most potent when they grow in symbiosis with birch trees, but the ones we used grew with pines. But the show wasn’t really an experiment, rather a proposition.

Did you not use the right kind of mushroom on purpose?

No, no.

But as a former scientist, wouldn’t you want to conduct a proper experiment?

Not really, but I think somebody should do it. We – there were a lot of people working on it – made the propo-sition to look for Soma and I hope somebody picks up on it. I had already tried the fly agaric before. They can be quite powerful. I’ve tried it six times. Sometimes there’s no effect, and sometimes it’s very strong. There’s a video of me under the influence where I’m singing.

You live here in Sweden. It is a strange place to be speaking about drugs, given the way people react to drug use.

Swedish politics can be really destructive towards the lives of people who have used drugs. I think everyone is free to experiment, to see what drugs can bring to him or her. The experiences can be amazing and very worthwhile to have as a reference point in your life. I was once in a discussion with the German ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch, who’s probably the world’s biggest expert on psychoactive plants. He asked me what the strongest psychostimulant I ever tried was, and I told him keta-mine – not the street kind, but medical grade ketamine. Then I asked what he thought one should try, and he replied that it’s definitely ayahuasca. It’s essentially DMT – dimethyltryp-tamine – that comes in a mixture of caapi vine extract and juice from leaves containing harmine. DMT acts very quickly, and lasts only for about ten minutes, but together with the harmine it lasts much longer. In Peru and other countries in South America, they use it for healing, he [Rätsch]said. The healer ingests ayahuasca and, looking at you, sees you in colours. If you have pain in your elbow, your elbow would be a different colour! It’s a technique they learn. Ayahuasca is a drug that arose from this healing perspective.

But it is also fashionable at the moment, to experiment with ayahuasca. Have you tried it?

I haven’t. And I really don’t understand where this trend is coming from. People are doing it even in Sweden.

Carsten Höller is often placed in the art-speak context of ‘relational aesthetics’, a term coined by French curator and Palais de Tokyo co-founder Nicolas Bourriaud. It’s used to describe art in the age after postmodernism: art not to be looked at or admired, but rather experienced – often transforming the spectator into an active participant in the work. Höller’s art is littered with references not to popular culture, films or music, as is common in contemporary art, but rather scientific or mystic theories and ancient religious texts, which launch the audience into the unknown, or at least the unexpected.

In Source Book, a set of texts collected by Höller and published to accompany Test Site, his monumental slide in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, he reproduces, amongst others, the words of René Daumal, a French poet and mysticist active in the Twenties, who put the case for the existence of a world beyond the one we see. By inducing near-death using carbon tetrachloride, an anaesthetic used to kill bugs before conservation, he repeatedly experienced a state of “another world, infinitely more real, an instantaneous and intense world of eternity, a concentrated flame of reality and evidence into which I had cast myself like a butterfly drawn to a lighted candle.” Daumal had this experience at the age of 16, then spent the rest of his literary life devoted to the search and conquest of this other world, perhaps more real than the one most of us take to be the real world.

Höller explains why he chose the text: “I’m interested in the idea that we, in our culture, have arranged ourselves around our perceptions. We seem to believe that the natural sciences and economic utilitarianism have worked so well that we have the world more or less under control. But I don’t think we’ve managed to control our inner world at all. Except from a medical perspective – which, of course, is very much linked to the natural sciences – there’s not that much we really know about it. It’s still very enigmatic. What is personality? Nobody knows. What kind of substance it has, nobody knows. Science speaks of neurons firing in certain ways, but what does that mean exactly – how does that produce feelings? I definitely think it’s worthwhile to look at it from a more mystic perspective.”

I can relate to drugs having mystic potential. In this post-ideological age, the constant pursuit of material accomplishment is lacking in reward. As we’re waking up to the realities of the failed promises of modernity, why not look to spirituality for answers? Höller’s answer is of his time. That the focus among contemporary intellectuals is on fly agaric and ayahuasca, and not LSD, seems perfectly logical, given the modern interest in organic lifestyles.

René Daumal also authored the seminal Mount Analogue. Written at the end of his life (in fact, he neverfinished it – the novel ends mid-sentence in chapter five), the novel traces an incredible yet entirely plausible search for the mountain of the same name. Daumal describes the mountain thus: “For a mountain to play the role of Mount Analogue, I concluded, its summit must be inaccessible but its base accessible to human beings as nature has made them. It must be unique and it must exist geographically. The door to the invisible must be visible.” In many ways, this sums up a lot of Höller’s ideas – every bit the former scientist, he no longer adheres to the so-called ‘Hippocratic Oath for scientists’ (see Höller’s series entitled Killing Children, made 1990–1994), and he remains preoccupied with the proposition of ‘something else’, something other than that which meets the eye.

You’re interested in other worlds and mysticism. Do you think everyday life is boring?

The matter isn’t whether it’s boring, it’s how much you feel you need your life to be under control. Once your life is under control, then you can allow yourself to explore, experiment, do things that are crazy. But most people have their lives so much under control and still they crave for more control. They are dependent on it. We have the luxury inside our rather privileged society to let some things go: it’s not going to be that damaging. Maybe it will fail. But the proposition is to make a common effort. Not that I, as an artist, will find the way and say “Let’s go over here, follow me!” That won’t work. It has to be done as a major effort on the part of society. It has to be a social experiment. You talked about Mount Analogue. It’s an important book for me – I’m actually writing about an expedition right now.

You’re writing a novel?

Yes.

Where?

Where? On my computer!

No, where is the expedition going to?

Oh, they’ll probably never leave. I don’t know yet. It’s about leaving logic behind – not logic as such, but what they call ThisLogic. It’s the logic of our way of handling life, our lives. It’s not properly explained in the novel, but it’s a kind of logic inherent to Western thinking, if you know what I mean. At the moment, there are three specialists in discussion – one is an art connoisseur, one is a specialist in hostage-taking, and the third is a scientist, a parasitologist. They’re the specialists, and then there will be participants, but I haven’t come up with those yet. It’s a work in progress.

Do you find it difficult to work with language?

No, I love it. But it was difficult in the beginning to find the voices of the characters.

What language are you writing in?

German. It’s the third time I’m writing from scratch. My characters aren’t going on a geographical expedition but, rather, are closing themselves off. They’re studying religious techniques, they’re looking at the Clausura, in which nuns are forbidden to speak or exit the convent, and stay inside reading the bible. You know about this?

I know monks do it. So they seclude themselves, stop speaking, read the bible, and then what?

Exactly. Then what? My characters are looking for the right place for this – and also for a place where not only spoken language, but also letters are banished – as an experiment on themselves. What happens if there is nothing more to read and nothing more to say? How do you think then?

—

One would be hard pressed to imagine Carsten Höller in seclusion. All the works in his latest show, Avec, at the gallery Air de Paris, were made not by Höller alone, but by Höller with someone – the someones in this case being Philippe Parreno (fellow artist), Ben Gorham (perfumer), Rigobert Nimi (model-maker), Yves Gaumetou (taxidermist), Attilio Maranzano (photographer), Francois Roche (architect) and two nameless twins. Höller’s much talked-about second home, in Ghana, is shared with video artist Marcel Odenbach. And Höller is often mentioned in the same breath as other artists of his generation, many also grouped under the relational aesthetics umbrella, such as Maurizio Cattelan, Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno, among others.

Though he doesn’t necessarily feel there’s a proper ‘group’ to speak of, Höller thinks the generational aspect is pertinent: “I’d say by pure timing, we were the last avant-garde artists. The death of avant-garde was something that Marcel Duchamp spoke about even in the Sixties, but now I feel that it’s a fact. I find it hard to see what else could be done, in terms of a major difference, in relation to what has been done already. Sports are the same – the only reason world records are still being broken is because they’re constantly inventing more exact measuring devices. And music? Nothing really new has happened since the birth of hip-hop. The only current avant-garde I can see is molecular cuisine, and even that is dying out now, because it proliferates so quickly.”

—

It’s interesting to note Höller’s obvious interest in, and connection to, fashion, a world built on the idea of newness. He has a close relationship with the Prada Foundation; among other collaborative projects, he has connected the floor of Mrs Prada’s office with the parking lot below (Scivolo n. 5 [Miuccia Prada], 2000) and run a bar/restaurant/nightclub in London financed by the Foundation (Double Club, 2008-2009). Carsten’s girlfriend, Naomi Itkes, is an accomplished stylist (and fashion editor of Bon), and Höller’s private views are as likely to be attended by his friends from Purple Magazine as critics from Artforum. The fashion world clearly has an interest in Höller and his work.

Is the feeling mutual? Are you interested in fashion?

I am, but I’m not an expert. I am mostly interested in the psychology of fashion. I don’t see a paradigm shift in fashion, either, at the moment – no new avant-garde. It’s a big machine now, not so ground-breaking like it used to be. It’s the same everywhere, a feeling that the big steps have been taken and now the legs are tied. A paralysed body that jerks frenetically, but doesn’t move.

Is that not quite a typical statement coming from someone who is, as you say, very much of your generation?

Of course, I would want to be proven wrong. I’ve maybe seen too much.

One could make the statement that, if anything, fashion is built on the new, with its new designers, new cities, new seasons…

Yes, but is it revolutionary? I always thought the fashion world has something unspeakable about it that I really like. If you come back to sports, for instance, sports you can measure, it has rules. You can have a discourse about art to some extent, philosophically at least. But not about fashion, really, it’s rather like a mass hysteria – it seems more like an organic thing. It spreads. An organism made out of human bodies. Am I wrong?

At least in the way fashion is perceived in the wider world…

It doesn’t even have to be high fashion. The amount of Converse shoes you see, it’s incredible! There’s something of a meta-organism about it, you see something more and more, everywhere, until it dies, and takes a new form. It’s almost like life forms: like pupae, something comes out of the old shell and is transformed.

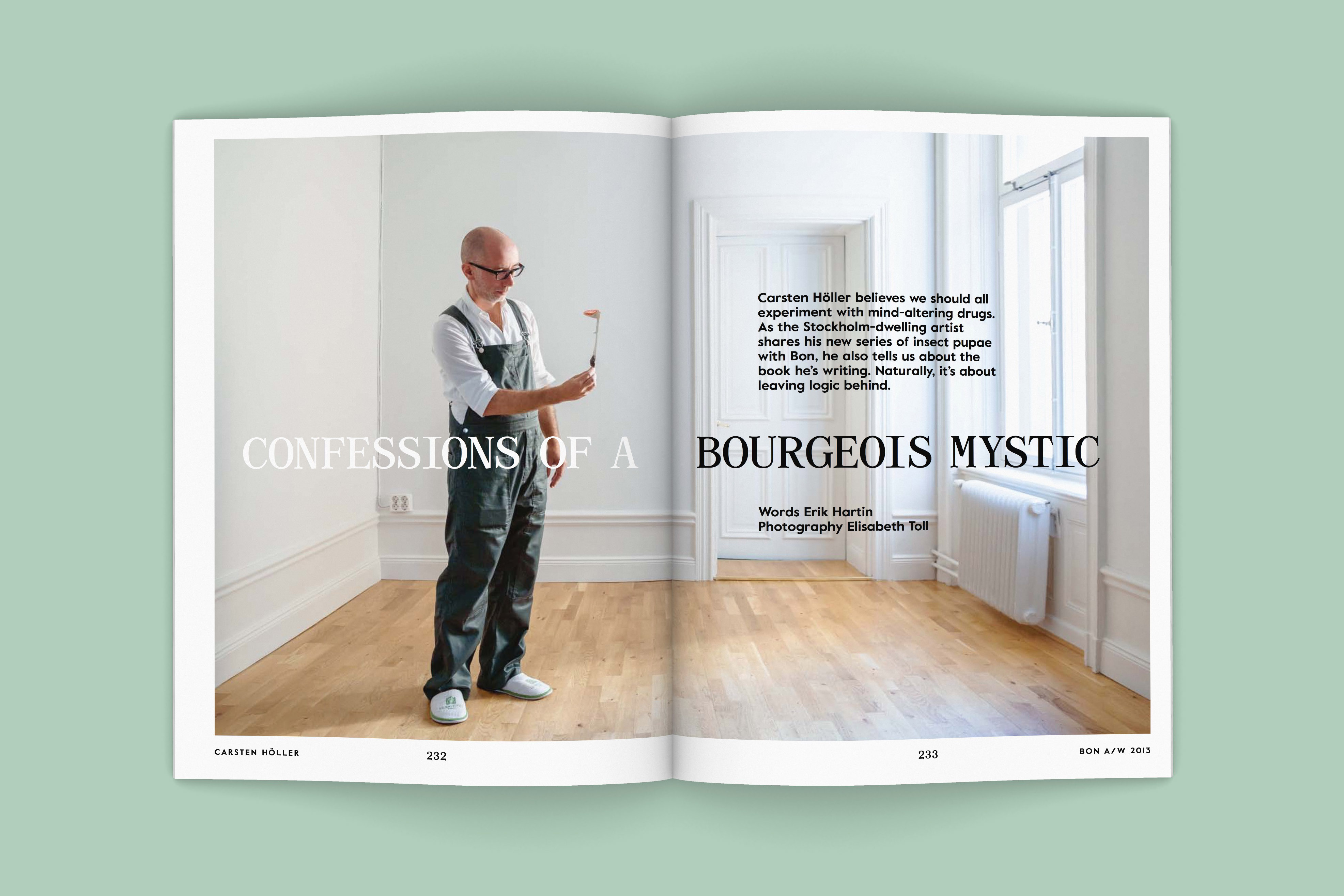

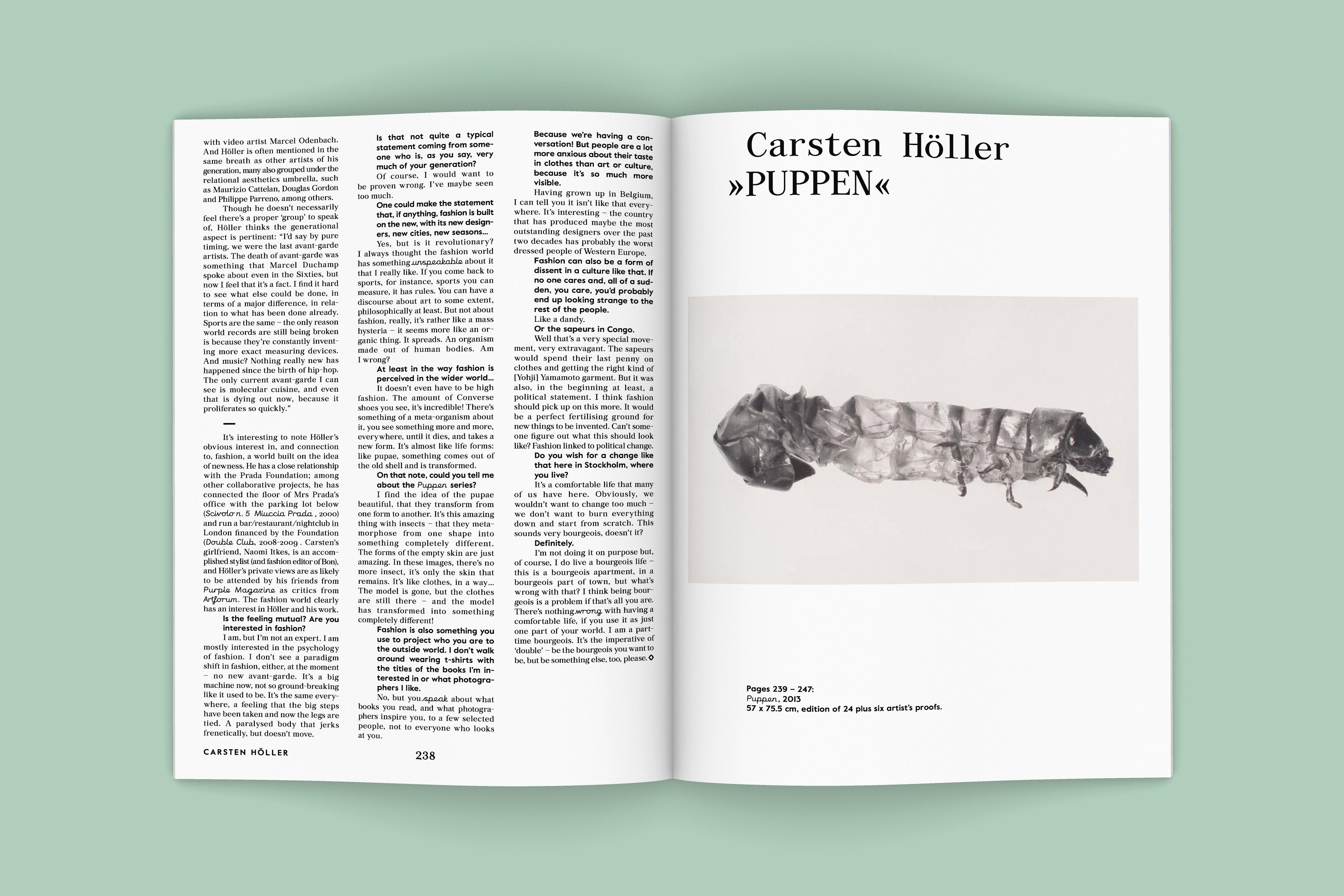

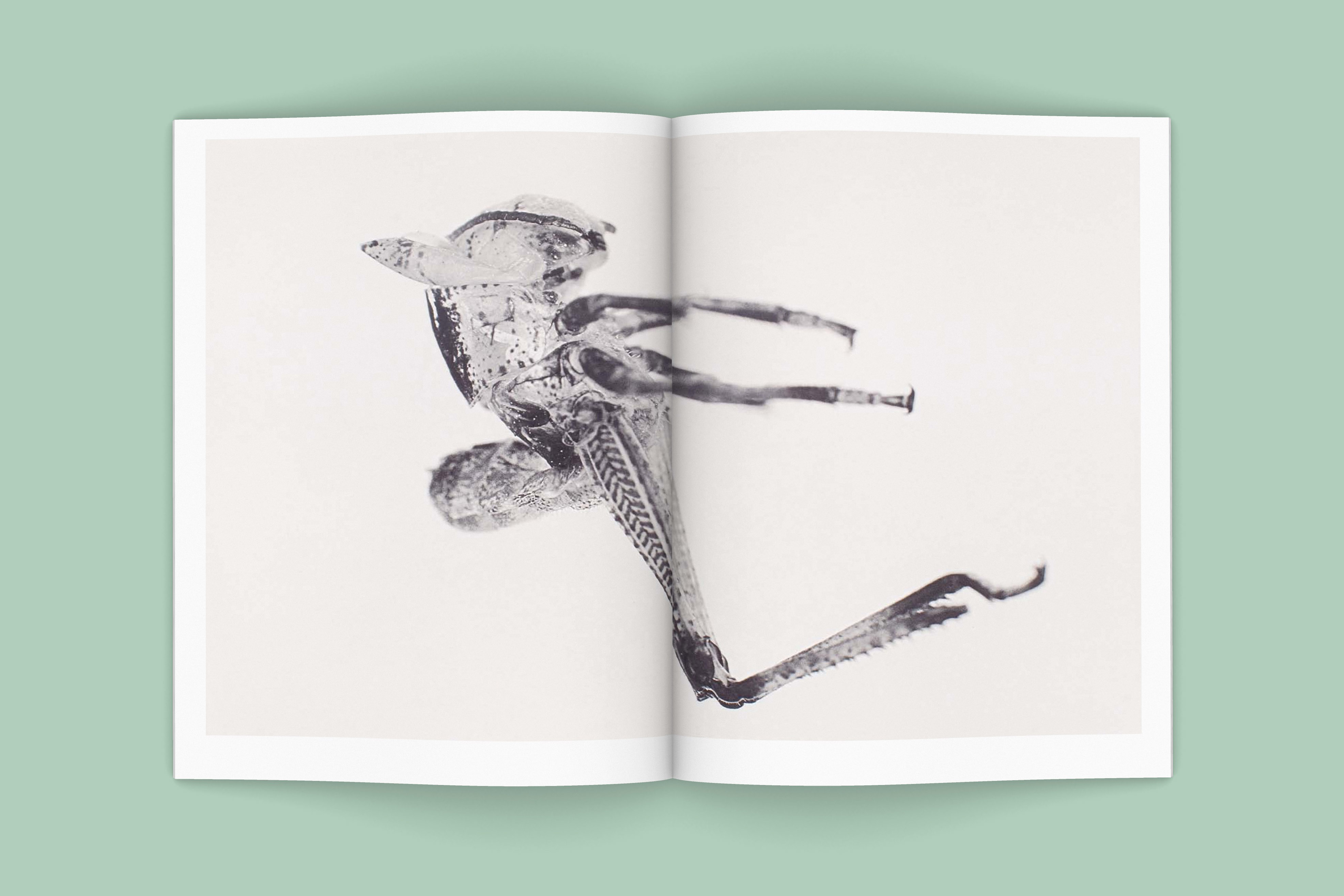

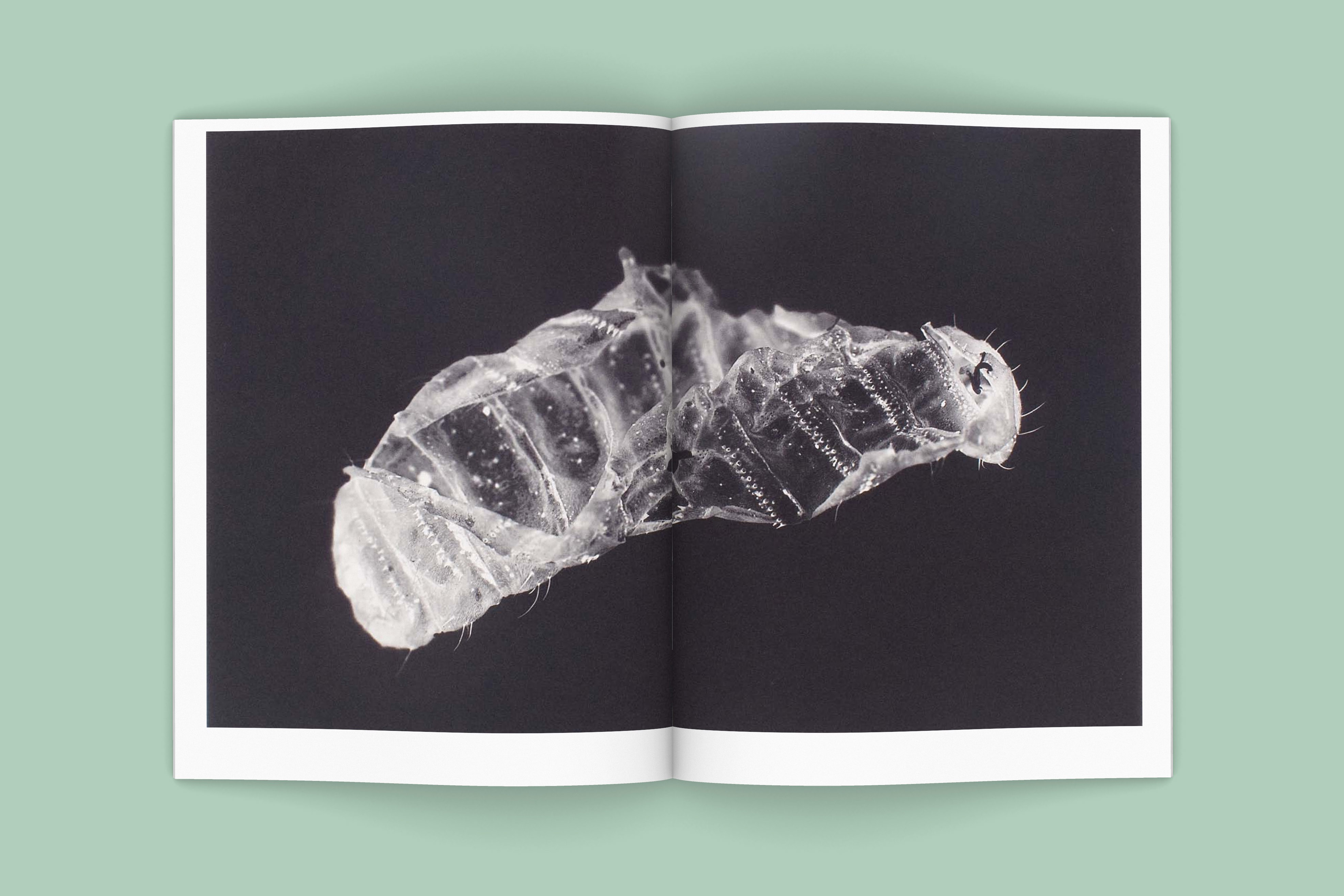

On that note, could you tell me about the Puppen series?

I find the idea of the pupae beautiful, that they transform from one form to another. It’s this amazing thing with insects – that they metamorphose from one shape into something completely different. The forms of the empty skin are just amazing. In these images, there’s no more insect, it’s only the skin that remains. It’s like clothes, in a way… The model is gone, but the clothes are still there – and the model has transformed into something completely different!

Fashion is also something you use to project who you are to the outside world. I don’t walk around wearing t-shirts with the titles of the books I’m interested in or what photographers I like.

No, but you speak about what books you read, and what photographers inspire you, to a few selected people, not to everyone who looks at you.

Because we’re having a conversation! But people are a lot more anxious about their taste in clothes than art or culture, because it’s so much more visible.

Having grown up in Belgium, I can tell you it isn’t like that everywhere. It’s interesting – the country that has produced maybe the most outstanding designers over the past two decades has probably the worst dressed people of Western Europe.

Fashion can also be a form of dissent in a culture like that. If no one cares and, all of a sudden, you care, you’d probably end up looking strange to the rest of the people.

Like a dandy.

Or the sapeurs in Congo.

Well that’s a very special movement, very extravagant. The sapeurs would spend their last penny on clothes and getting the right kind of [Yohji] Yamamoto garment. But it was also, in the beginning at least, a political statement. I think fashion should pick up on this more. It would be a perfect fertilising ground for new things to be invented. Can’t some-one figure out what this should look like? Fashion linked to political change.

Do you wish for a change like that here in Stockholm, where you live?

It’s a comfortable life that many of us have here. Obviously, we wouldn’t want to change too much – we don’t want to burn everything down and start from scratch. This sounds very bourgeois, doesn’t it?

Definitely.

I’m not doing it on purpose but, of course, I do live a bourgeois life – this is a bourgeois apartment, in a bourgeois part of town, but what’s wrong with that? I think being bourgeois is a problem if that’s all you are. There’s nothing wrong with having a comfortable life, if you use it as just one part of your world. I am a part-time bourgeois. It’s the imperative of ‘double’ – be the bourgeois you want to be, but be something else, too, please.

Naomi made me do it.