I first met Lina Scheynius on a sunny day in Paris in 2008. She was strolling down the Canal Saint-Martin with her best friend Amanda, and the combined height of the pair, who are often mistaken for each other, made me assume they were models. Shortly thereafter, I was introduced to Lina’s photographs, and though I could see that I wasn’t completely wrong (they had both beenmodels) the world that opened up through her work was one of an artist: flooded in warm sunlight, her visual universe was, already at the beginning of her career, at once fragile and confident, funny and sad, sensual and violent—and always beautiful.

Lina’s work was quickly appropriated by the fashion world, and she found herself taking photographs for magazines such as Vogueand Another. But in 2014, she decided she needed a break from the stress that her career imposed on her, and she went back to her native Sweden to take self-portraits and develop her personal practice. These days she only occasionally produces work for clients, and only under conditions that she herself dictates. No longer subjected to fashion editors interfering with the hems of Lina’s subjects, she prefers to work alone.

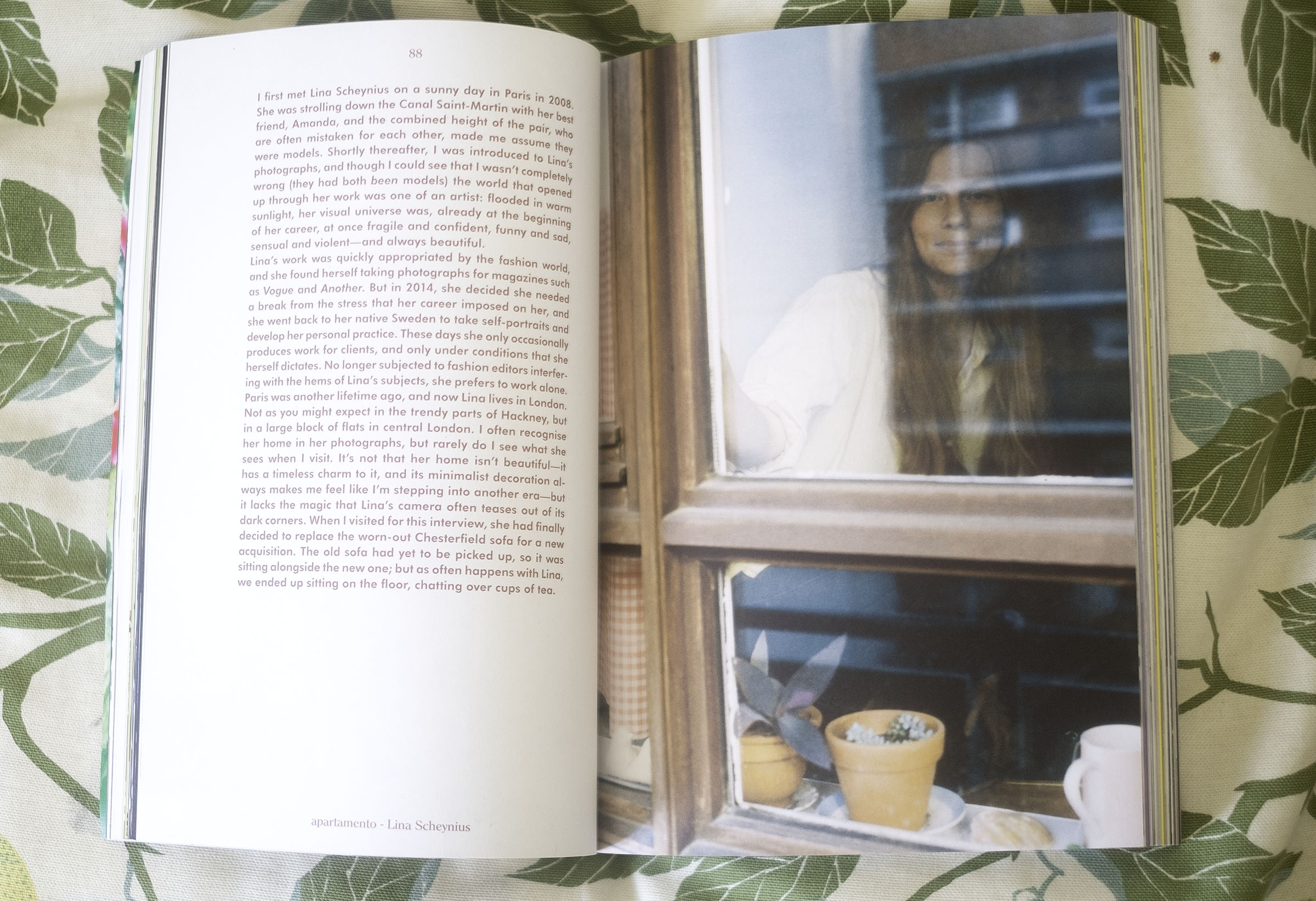

Paris was another lifetime ago, and now Lina lives in London. Not as you might expect in the trendy parts of Hackney, but in a large block of flats in central London. I often recognise her home in her photographs, but rarely do I see what she sees when I visit. It’s not that her home isn’t beautiful—it has a timeless charm to it, and its minimalist decoration always makes me feel like I’m stepping into another era—but it lacks the magic that Lina’s camera often teases out of its dark corners. When I visited for this interview, she had finally decided to replace the worn-out Chesterfield sofa for a new acquisition. The old sofa had yet to be picked up, so it was sitting alongside the new one; but as often happens with Lina, we ended up sitting on the floor, chatting over cups of tea.

Do you rent your flat furnished?

Yes. It’s the same furniture as when I moved in. I do own some of the furniture: the chair by the desk is mine, and the bed. Not that I would bring them with me if I moved. The plants are mostly my landlord’s. When I moved in it was supposed to be for six months and he wanted me to look after them.

You don’t seem very attached to your things. It’s very un-Swedish of you; Swedish people in general seem to care a lot about furniture.

They do! But I don’t, really. No, I do care about furniture a lot, but I think I care more about feeling free, and as I am renting this second-hand I can’t care too much about my furniture at the moment.

This flat shows up all the time in your photographs. It’s almost like people would know what your home looks like just from looking in your books and at your Instagram feed. But you’re also a deeply private person. How do you feel about that—that strange people know how you live?

Do you think so? I feel like maybe now they will, after seeing Alba’s photographs. But I don’t feel like I really show my home in my pictures. Nobody knows what books I have.

It’s also a bit strange to be here at night. Your photos from here are almost always taken when the flat is bathed in sunlight. And I’m usually here in the daytime. Now you have drawn this big blind across the window.

I usually keep it down at night, otherwise it feels like putting on a show for the neighbours; they are so close. Do you want to experience it?

I think we should!

I used to have a flatmate, Amanda. She stayed in this room and would always walk around naked.

Amanda is always naked in your pictures.

Yes, that’s what she’s like in real life. There, now everyone can see us. I find this a bit awkward. Do you keep the blinds drawn in your home?

No, and my neighbours are much closer than yours.

And you don’t care?

No. I feel like there’s a neighbour exception. If you meet a neighbour from across the road on the street, you wouldn’t say hello even if you’ve seen them through their window a thousand times. It would be an invasion of privacy.

There’s a couple across from me who are so irritating. They’re always on their balcony, fighting. I can recognise their voices in the street. I even see them in central London! But I’d never say hi to them. I hate them.

You say you don’t want to put on a show, but you often use yourself as a model in your photos. Why is that?

I don’t really know. I usually say that it’s because I’m always around when I want to take pictures. I don’t think that’s true though.

Do you use your friends as models?

Not so much, no. I suppose I could take a lot more pictures of them if I wanted to. But I really don’t think they’d be up for it. In the end, I think it’s easier to take pictures of myself.

It doesn’t sound like you’re that interested in showing yourselfnecessarily.

When I photograph other people, there are often things that I would like to try that I’m not really comfortable asking them. Or I feel like they’re doing me a favour—or even stranger, sometimes I feel like I’m doing them a favour.

So it’s transactional?

Yes. But with myself I can just try whatever I want, and if I don’t like it afterwards, that doesn’t matter. The only thing I risk is having to look at myself in a horrible position afterwards.

Do you discover things about yourself through your self-portraits?

Yes. I have discovered how I am ageing.

In what way?

In spring 2015 I was going through a nervous breakdown, and I was taking one roll of film every day for about 60 days. When I developed the films halfway through, I realised the photos weren’t very flattering. I thought I looked so old.

How do you feel about them now?

More that I look very tired and lifeless. But at the time, I thought I looked horrible and old, wrinkly.

Thinking about how you use your own body in your work, it’s a way of working that has turned into a quite politicised statement by woman artists, especially younger ones, working with photography. You’ve actually been doing this for a very long time, so I was curious whether you see yourself attached to this, as a movement of sorts?

There was a kind of before and after, when people started to ask me about feminism, as related to my work. A few years ago people would say that showing nude female bodies would be degrading to women. Someone actually told me, ‘You shouldn’t show yourself naked’. That’s totally insane. But now people ask me about my thoughts on feminism.

What are your feelings about feminism in relation to your work?

I don’t know. It’s not like I need to do this because I’m a feminist. I exhibited a period-blood photo in Paris once, and people thought it was about rape—the photo was of a bloody penis.

Do you often get objections about your work? You’re very active on Instagram, and women showing their bodies on Instagram tend to attract horrible men.

Not so much. I’m actually shocked how nice everyone is to me. Can we draw the blinds again? I feel uncomfortable.

What’s the difference between the people in the building over there looking at you versus some person you don’t know on the internet?

Maybe because this right here is happening live and I can’t control it. With my work, or on Instagram, I feel in control.

You also exhibit your work in galleries. Is that different from sharing your pictures online?

I’m much more comfortable on Instagram. In the gallery, I feel quite foreign. And I’m physically present alongside my work. On the internet, I might show images of my vagina or myself crying but I’m not literally standing next to them.

Maybe you shouldn’t go to your own private viewings! But, still, you like the physical aspects of photography, don’t you? You always make prints, and only shoot on film.

I like the little prints, the postcard-size ones. I use them when I edit my photos.

I find the small prints quite weird. The fact that they exist as physical images makes them precious in some way, but then again they’re not; they’re just raw unedited photographs. I have a box of small prints from when I lived in Paris that I don’t know what to do with.

Don’t throw them away!

Why not? I have all the negatives.

But you’re not going to look at the negatives!

But I don’t look at the prints either. Of course, they’re great if you want to sit around and look at them and be nostalgic.

Yes, that’s wonderful! That’s what they’re for.

Do you see your pictures as documentation?

In a way. Of people I’ve known, places I’ve been, smells. Even if someone were to tell me, ‘Tomorrow you’re not a photographer anymore’, I would still want to keep all my prints. I’ve never thrown away a print.

Even the ones you don’t like?

Yes. I guess I’m a photography hoarder.

Do you hoard other people’s pictures?

No. Except I have scanned some of my dad’s slides—and I have a big pile of my great-grandfather’s photos over there that I found in a drawer in Sweden. I’m editing them for an exhibition. Or maybe a book.

Who was your great-grandfather?

A Lithuanian writer called Scheynius. The photos are from after he moved to Sweden, in the ‘20s.

You’ve also been posting a few of your dad’s photos on your Instagram. Everyone loves them.

Yes, they’re great! Maybe I could make a book.

You have made a lot of books. There are 10 now, which you have edited and designed yourself. When did you decide to start self-publishing your work?

In 2008. I had really wanted to make a book for a while, and after thinking it over I realised that maybe people would want to buy it. So for the first one, I chose photos that I knew people liked.

The books are all the same format, with a white cover, and when I see them all together on the shelf over there, they kind of look like one, albeit very long, book. Your books are never a document of a single event; you might have photos that are 10 years old alongside new work. But, on the other hand, a single book is contained: it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How do you choose what goes into a book?

That’s the scary part. I think they are very different. The first book was really easy to edit. Like I said, I selected pictures that I knew people really liked, mostly Polaroids. When I decided to continue, at some point I would just feel that, OK, I think I have enough pictures to make a book. But, again, I sometimes do jump back in time, like in book number three, I selected pictures taken ages ago.

But how do they differ from one another to you? Could you describe book number five?

It has double-page photos. People complained about that.

People have opinions on your layout choices?

Yes. And I don’t think I’ve used double-page photos after that. Except for a few in book seven.

Tell me about the last one, number 10. It’s very different from the previous ones, in that it tells the story of your relationship with your ex, Emeric.

I had been working on a book about my two years in Paris, but I felt stuck. I realised that the photos were kind of boring to me, like postcards. As a way of making it more interesting, I considered using old diary entries from the time. I brought them into the book and showed it to David, my boyfriend after Emeric. It was really private and a bit embarrassing. He read it and said he thought it was good and suggested that I remove everything that wasn’t about Emeric—to make the book only about him.

Was it strange to you that your boyfriend was encouraging you to create a book about your ex?

It felt very awkward to ask him to read it. I warned him many times, ‘Are you sure you want to read it? It’s going to be really graphic and it might be weird for you’. But once he’d read it, it wasn’t that strange. I trust him with words; he had helped me edit my writing before.

You worked as a model for a long time. When did you decide to become a photographer?

My dad gave me a point-and-shoot camera when I was 10 years old, and I studied photography when I was in sixth form. I didn’t really take many photos of the model flats or the other models when I was modelling, but that’s the time when I started to take pictures of friends and ex-boyfriends, and also the naked self-portraits. I did this very much for myself over many years and only showed the pictures to a few friends. Then I found and joined Flickr at the end of 2006, and then things happened very fast. I got my agent through Flickr. And in 2008 I moved to Paris with my friend Amanda and decided to stop modelling and become a photographer.

And what happened after that?

Just after signing with the agency I got a job shooting Charlotte Rampling. I photographed her in my flat in Paris. And after that things started happening really quickly.

You have a quite unique aesthetic. It’s not hard to spot a Lina photograph. Was it ever a conscious decision for you, that ‘this is how my photos should look’?

At some point they just started to look like something I liked. Honest maybe, or raw. I stopped using a flash—that helped my photos a lot.

Are you influenced by other photographers?

I really love Nobuyoshi Araki’s work. I found Self Life Deathat Foyles, and I got my parents to give it to me for Christmas. They were shocked when we opened it together!

Are your parents ever shocked by your work?

My mum makes jokes about it. She’s got pretty dry humour. She came to an exhibition I was featured in, in Berlin. There were only photos of naked men, so whenever I invite her to an exhibition now, she says, ‘Oh, it’s not going to be just naked men again, is it?’

And what about your dad?

He’s really supportive, he always wants to come if I have a show. And he was the one encouraging me when I was little, buying me film and developing photos. He paid for the printing of my first book. But I paid him back once I sold them all.

You seem to always want to do everything yourself, including your own books. Have you been approached by publishers at all?

Yes. Sometimes I string them along for a while. But I haven’t found one yet that I like. I always come back to thinking I can do it myself instead.

I’ve noticed, like on your Instagram account, that people keep asking you very technical questions: what camera you use, what aperture, and so on.

Yes. I don’t get it.

What else do people ask you? Do they ask about you or your friends or your work?

Let’s have a look. This one is good: ‘Hi, Lina, I’ve been a huge fan of your work since your Flickr days […] I remember you were in a top [photographer] agency. I’m very curious about why you quit all that, to be on your own now. Lots of love’.

That’s a great question! Did you reply?

I did. ‘Hey, and thank you. I quit because I wanted to be an artist and work on personal things that mattered to me. At first the plan was to take just one year off. But I didn’t feel inspired to get back to it, so it became many more. PS your work is really good’.

Did you get a reply?

I did. ‘Oh, thanks, Lina. That was a brave decision. Actually most people would do the opposite’.

I can see how you think Instagram provides a really positive experience for you!

More technical questions: I posted a photo of some film and someone asked how much I paid for it. Another person wrote, ‘Hi, Lina, I bought a book of yours and I wanted to ask where you printed it? I want to make one for my girlfriend and I like yours so much’. That gets asked a lot. Let’s do this one: ‘How do you make your self-portraits? Do you use a selfie stick? Do other people take them for you? A tripod?’

That’s like something you would ask a fashion blogger.

I use a tripod. I hate it when other people are around.

It’s interesting with your self-portraits because they are often quite performative. How doyou make them? Do you take 10 photos in one go and choose the best one?

It depends. If I am in a hotel room on my own I can just start making self-portraits. At one point I started going to random places and checking into hotel rooms so that I would get more pictures.

Really? Where?

I went to Antwerp. That’s where I did the rainbow-vagina picture. I also went to Brussels. I made at least three trips like that. I was thinking yesterday that I wanted to go back to the Antwerp hotel because they had a black bathtub. I really liked the photos I made there because that was really unusual.

Did you see anyone when you went on those trips?

No. I needed to be away without distractions. Should we do one last Instagram question? I haven’t replied to this one: ‘I always wanted to ask you what you think your work is about’. I can’t answer that question.

You can try! What is your work about, Lina?

I have a new theory that it might be about vulnerability.

Yours or in general?

Isn’t it the same?

If you’re an artist it could be, I suppose. Do you see yourself as an artist?

No. I’m a photographer. I’m not ready to wear those shoes.

Interviewing a friend is difficult, but incredibly liberating. After having known – and worked with – Lina for many years, she asked me if I wanted to interview her for Apartamento (or I asked if I could, I forget the sequence), but with a word count and a deadline, things are different. It was very interesting, being able to ask questions that might be too private even for a friend, in the interest of journalism. I wish I could do this with (or to) all my friends.